Malnutrition in the developing world...

...has halved in the last 40 years

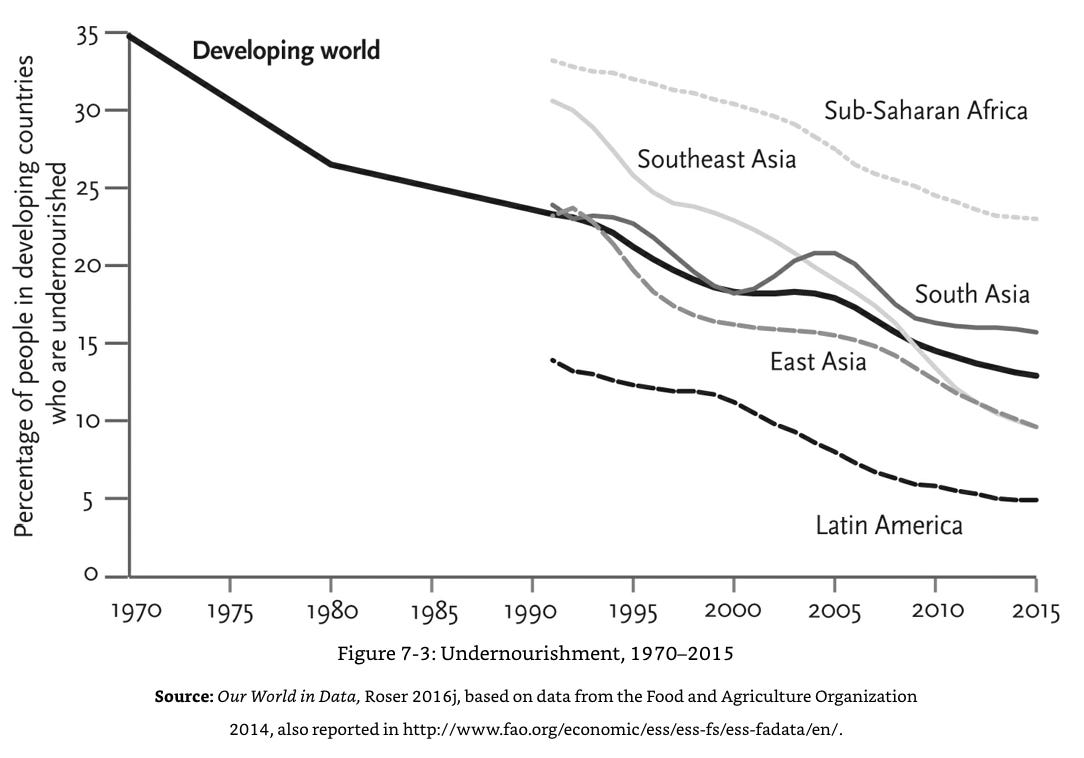

In the 1960s several books were written about the ‘population bomb’ - a geometrically increasing population combined with a linearly increasing food supply would result in starvation around the world. But the books were wrong on both counts - as we’ve seen, population starts to stabilise as child mortality rate decreases, and we’ve tripled the amount of food we can produce on a given area of land. As a result, malnutrition has massively decreased in the developing world in the last 40 years (it was already extremely low in developed countries).

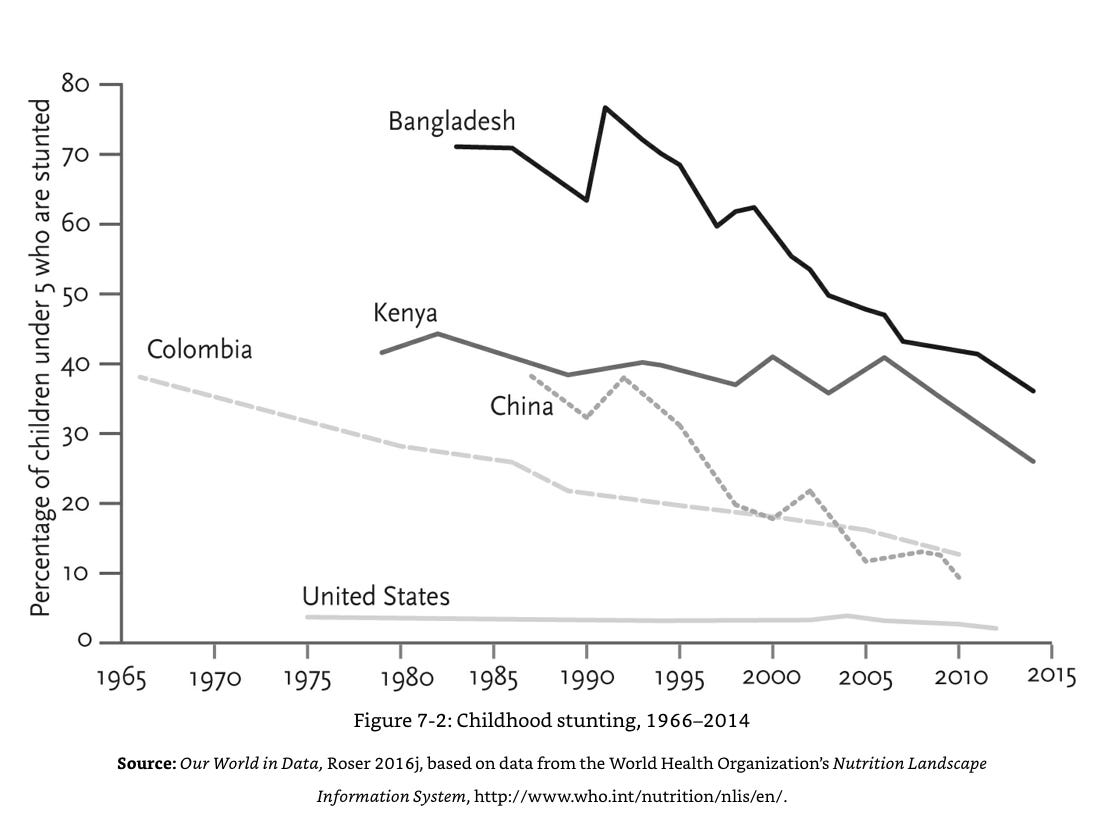

Here’s a related graph that I think more than any other I’ve come across illustrates the ‘bad but better’ conundrum:

My first thought, looking at the y-axis on this graph, is that a 20-30% rate of stunting (a growth problem highly related to nutrition) in children is horrifically high. But then I look at the change in these countries from just 20-30 years ago and see the phenomenal achievement of halving that rate in just a few decades, when it has been the default state of the whole of humanity for millennia.

This is the in-built contradiction of a clear-eyed examination of progress data. Many things are still very bad, but many of those same things are far better now than they have been even in the recent past. Those improvements, however, haven’t happened by magic. They have happened because of technological developments, societal structures and the hard work of millions of individuals. We should take heart at the positive changes we’ve achieved, but also use them as a spur to continue to make things better.

Source: Enlightenment Now, Stephen Pinker